Boyle's law

Boyle's law (sometimes referred to as the Boyle-Mariotte law) is one of several gas laws and a special case of the ideal gas law. Boyle's law describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system.[1][2] The law was named after chemist and physicist Robert Boyle, who published the original law in 1662.[3] The law itself can be stated as follows:

For a fixed amount of an ideal gas kept at a fixed temperature, P [pressure] and V [volume] are inversely proportional (while one increases, the other decreases).[2]

Contents |

History

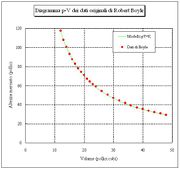

This relationship between pressure and volume was first noted by two amateur scientist, Richard Towneley and Henry Power. Boyle confirmed their discovery through experiments and published the results. According to Robert Gunther and other authorities, it was Boyle's assistant Robert Hooke, who built the experimental apparatus. Boyle's law is based on experiments with air, which he considered to be a fluid of particles at rest, with in between small invisible springs. At that time air was still seen as one of the four elements, but Boyle didn't agree. Probably Boyle's interest was to understand air as an essential element of life;[4] he published e.g. the growth of plants without air.[5] The French physicist Edme Mariotte (1620-1684) discovered the same law independently of Boyle in 1676, but Boyle had already published it in 1662, so this law may, improperly, be referred to as Mariotte's or the Boyle-Mariotte law. Later (1687) in the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica Newton showed mathematically that if an elastic fluid consisting of particles at rest, between which are repulsive forces inversely proportional to their distance , the density would be proportional to the pressure,[6] but this mathematical treatise is not the physical explanation for the observed relationship. Instead of a static theory a kinetic theory is needed, which was provided two centuries later by Maxwell and Boltzmann.

Definition

Relation to Kinetic Theory and Ideal Gases

Boyle’s law states that at constant temperature for a fixed mass, the absolute pressure and the volume of a gas are inversely proportional. The law can also be stated in a slightly different manner, that the product of absolute pressure and volume is always constant.

Most gases behave like ideal gases at moderate pressures and temperatures. The technology of the 1600s could not produce high pressures or low temperatures. Hence, the law was not likely to have deviations at the time of publication. As improvements in technology permitted higher pressures and lower temperatures, deviations from the ideal gas behavior would become noticeable, and the relationship between pressure and volume can only be accurately described employing real gas theory.[7] The deviation is expressed as the compressibility factor.

Robert Boyle (and Edme Mariotte) derived the law solely on experimental grounds. The law can also be derived theoretically based on the presumed existence of atoms and molecules and assumptions about motion and perfectly elastic collisions (see kinetic theory of gases). These assumptions were met with enormous resistance in the positivist scientific community at the time however, as they were seen as purely theoretical constructs for which there was not the slightest observational evidence.

Daniel Bernoulli in 1738 derived Boyle's law using Newton's laws of motion with application on a molecular level. It remained ignored until around 1845, when John Waterston published a paper building the main precepts of kinetic theory; this was rejected by the Royal Society of England. Later works of James Prescott Joule, Rudolf Clausius and in particular Ludwig Boltzmann firmly established the kinetic theory of gases and brought attention to both the theories of Bernoulli and Waterston.[8]

The debate between proponents of Energetics and Atomism led Boltzmann to write a book in 1898, which endured criticism up to his suicide in 1906.[8] Albert Einstein in 1905 showed how kinetic theory applies to the Brownian motion of a fluid-suspended particle, which was confirmed in 1908 by Jean Perrin.[8]

Equation

The mathematical equation for Boyle's law is:

where:

- p denotes the pressure of the system.

- V denotes the volume of the gas.

- k is a constant value representative of the pressure and volume of the system.

So long as temperature remains constant the same amount of energy given to the system persists throughout its operation and therefore, theoretically, the value of k will remain constant. However, due to the derivation of pressure as perpendicular applied force and the probabilistic likelihood of collisions with other particles through collision theory, the application of force to a surface may not be infinitely constant for such values of k, but will have a limit when differentiating such values over a given time.

Forcing the volume V of the fixed quantity of gas to increase, keeping the gas at the initially measured temperature, the pressure p must decrease proportionally. Conversely, reducing the volume of the gas increases the pressure.

Boyle's law is used to predict the result of introducing a change, in volume and pressure only, to the initial state of a fixed quantity of gas. The before and after volumes and pressures of the fixed amount of gas, where the before and after temperatures are the same (heating or cooling will be required to meet this condition), are related by the equation:

Boyle's law, Charles's law, and Gay-Lussac's law form the combined gas law. The three gas laws in combination with Avogadro's law can be generalized by the ideal gas law.

See also

- Avogadro's law

- Charles's law

- Combined gas law

- Gay-Lussac's law

References

- ↑ Levine, Ira. N (1978). "Physical Chemistry" University of Brooklyn: McGraw-Hill

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p12 gives the original definition.

- ↑ J Appl Physiol 98: 31-39, 2005. Free download at Jap.physiology.org

- ↑ The Boyle Papers BP 9, fol. 75v-76r at BBK.ac.uk

- ↑ The Boyle Papers, BP 10, fol. 138v-139r at BBK.ac.uk

- ↑ Principia, Sec.V,prop. XXI, Theorem XVI

- ↑ Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p11 notes that deviations occur with high pressures and temperatures.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Levine, Ira. N. (1978), p400 -- Historical background of Boyle's law relation to Kinetic Theory